On the occasion of the World Environment Day on the 5th of June, we invite you to meet Pr. Chris Portier, whose entire career has been devoted to protect people from environmental hazards.

Former Director of several US agencies, he has been a member of numerous World Health Organisation (WHO) and International Agency for Research on Cancer (IACR) scientific committees, and has contributed to various scientific reviews and risk assessments.

Back in the early 90s in the US, he was given the task to analyse causality between power lines and child leukaemia. With a group of scientists, he conducted various studies that led to changes to avoid magnetic fields and electric fields at home.

In 2009, he launched and coordinated a research to urge the need to study the impact of climate change on human health. The report called “A Human Health Perspective on Climate Change” published in April 2010 highlights the impact on climate change for reproductive health, development risk, cancer, respiratory diseases for instance. The authors received a Presidential Award for this publication that led to label climate change not only as an ecological problem but also as a public health issue in the US.

Pr. Portier is also renown in Europe and in the US for speaking up against glyphosate in 2017 in a hearing in the European Parliament, as an expert of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) which classified glyphosate as possible carcinogen for human in 2015. His intervention participated to improve the practice of regulators when conducting safety assessment of chemicals.

Chris Portier is now the chair of the Stakeholder Advisory Board of PrecisionTox, an EU-funded project whose objective is to accelerate risk assessment of chemicals without using vertebrate models, which intends to improve public health and environment policies and to reduce animal experiment.

In 2017, you explain to the Members of the European Parliament how the EU regulators failed to identify the carcinogenicity of glyphosate for human. How come the US Environment Protection Agency (EPA), the European Chemical Agency (ECHA) and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that glyphosate was not likely to cause cancer in human while IARC reach another position?

“I don’t think the EU and US regulatory agencies did as good a job reviewing the epidemiology as IARC did. I believe the regulatory agencies did not follow their own rules for how to do the evaluation and missed a lot of things.

The reviews at IARC are done by independent scientists who come from outside. They take a year to review the literature from their home institutions, and then they come to the office for eight days to debate, rewrite and, come to conclusion. IARC uses about eight epidemiologists for every review they do when most regulatory agencies have one. IARC uses world renowned toxicologists to help review publicly available data only. In ECHA, EFSA, US EPA, it is staff that do the evaluation, the same people who rely very heavily on data provided by industry. They put less weight on the information from the published peer reviewed literature, and they don’t do a very good job with the epidemiology.”

Would you say that since this affair, practices have changed at the regulatory level?

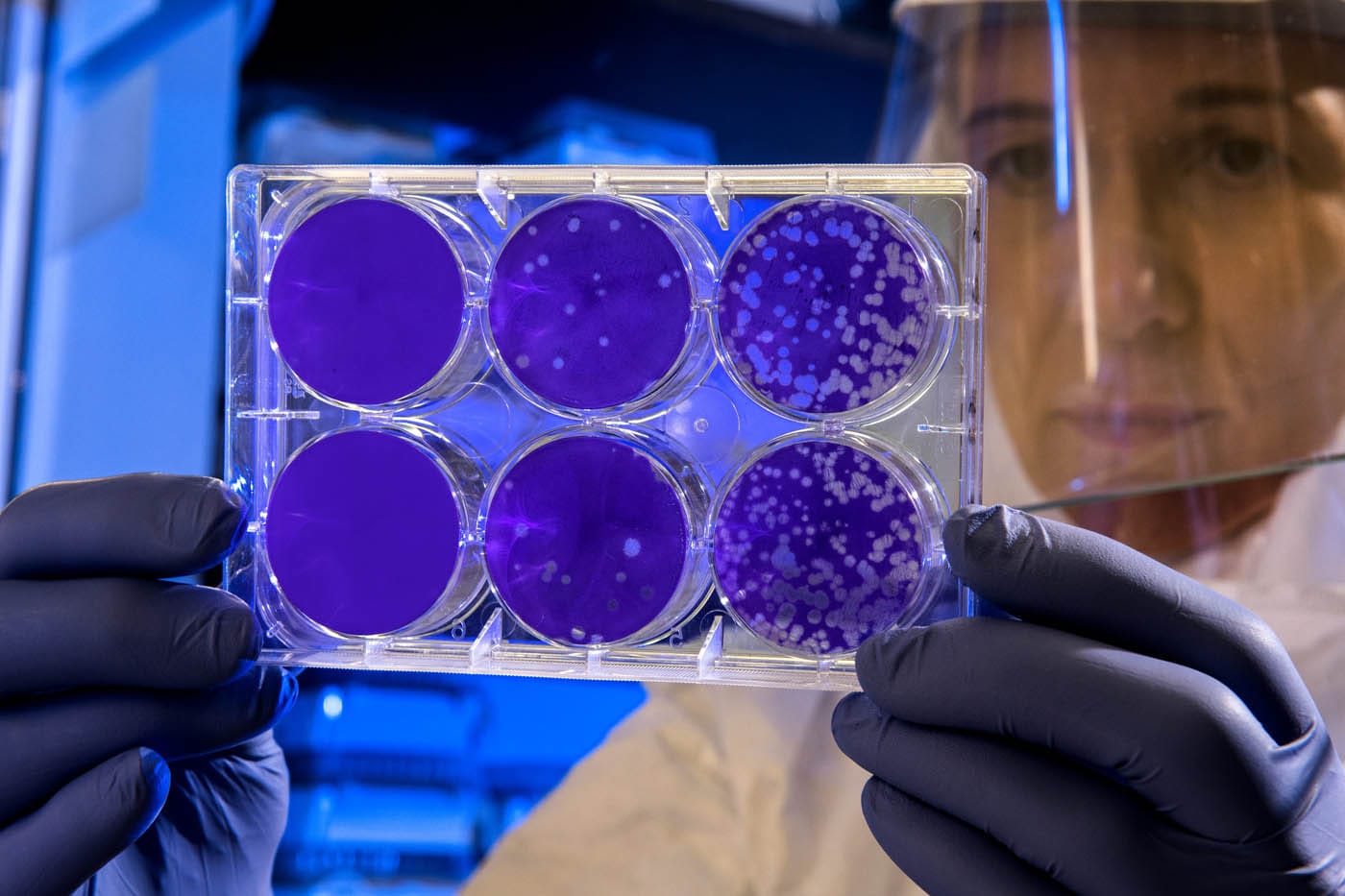

“Yes, it did, the data that they rely on, which is generally animal studies, is no longer proprietary and will have to be released from now on. That’s a big deal. If you think of what the PrecisionTox project is trying to do by developing non vertebrate models, you want to be able to show that we can actually predict what you already know for a variety of chemicals. You need animal cancer studies, if you’re going to try to predict cancer. The biggest data set of animal cancer study that is publicly available is the National Toxicology Program’s database. If that data gets released, we have got a whole wealth of knowledge to help validate alternatives to animals.”

You are referring to PrecisionTox, an EU-funded project aiming to improve safety assessment of chemicals without using vertebrate models for which you are the chair of the Stakeholder Advisory Board. How can non-mammalian safety testing can help advance toxicology and can impact the environment and health policies?

“Regulatory policy does not change very rapidly. Yet, we have thousands of chemicals that we are exposed to. Even if we wanted to do animal studies for all of them, we cannot, it is just too big of a task. We have to find something that will move faster, be more effective and get us information that we can make decisions on right away.

Back in 2003, when I was running the US National Toxicology Program (NTP), I asked myself a simple question: if I was to build a US National Toxicology Program to date, does the program I have match what I would build? The answer was no.

We were heavily focused on long term exposure to animals, and the science had moved on. Molecular biology had tremendously advanced, and we weren’t taking that into account in the regulatory science. We rewrote the way the NTP was going to work for the next 10 years, with the objective to move toxicology from an observational science to predictive science and that we would do a predominant amount of our testing in either cells or non-vertebrate species.

A lot of money and efforts were put into that initiative which let TOX21, a collaboration between several federal agencies to develop new ways to rapidly test whether substances adversely affect human health. Its goal is to provide a series of tools that allow to seriously reduce the use of animals. We are still probably going to have to use some animals in regulatory testing, but hopefully we can reduce it quite a bit, if we can get a series of models that predict what we already know.

And that is what PrecisionTox is aiming at, the consortium led by the University of Birmingham complements what the NTP and the EPA are doing in the US.”